Overview

Hummingbirds (Trochilidae) have the fastest metabolism, they are the smallest in the bird world, they can fly backwards, and they can hover without a headwind. Their wingbeat frequencies vary with the size and species of the bird and the elevation above sea level. While some evaluations of wingbeat frequencies have been performed, few have concentrated on species which commonly occur in Southern California.

The development of high-speed video technology over the last couple of decades has increased radically in performance and decreased as radically in cost. High-speed cameras are now capable of ten million frames per second, and even an iPhone can shoot at 240 frames per second. For this project, I had access to an iX Cameras i-SPEED 726 camera – significant overkill in terms of performance, but extremely easy to use for capturing calibrated footage enabling extensive hummingbird wingbeat analysis.

Background

Calculations for Capturing ‘Frozen’ Images of Hummingbirds in Flight

I have been photographing still images of hummingbirds in flight for over 20 years. I have shot both film and digital images in 35mm and larger formats, totaling more than 650,000 pictures. My aim is to ‘freeze’ the motion of the birds’ wings to reveal the exquisite details of even the tiniest feathers. To achieve this, I developed my own high-speed flash system. When I started designing, my literature research revealed an ‘average’ wingbeat frequency of 80Hz. I saw this number in several publications in the mid-1990s, and took it to be accurate. This resulted in the following design parameters for the flash system:

- Wingbeat frequency: Approx. 80Hz, as quoted in numerous texts and sources

- Full Wing Flap Amplitude (peak to peak): Approx. 4 inches

- Acceptable blur at wingtip at maximum velocity (mid-flap): 1/20th of an inch

- Thus, in a full second, the distance travelled by a wingtip is 80 x 2 x 4 = 640 inches

- For acceptable blur of 0.05 inches, the flash duration could not exceed 0.05/640 = 78µs

The Fotronix StopLight SL-80 was specifically designed in 2002 for photographing hummingbirds. The units had a flash duration of around 60µs, were waterproof, portable and very successful. The images produced were state-of-the-art, with wingtips frozen in time. Contemporary high output flash units such as the Paul C Buff Einstein can create very short flash durations with very usable output levels by utilizing IGBT technology. An Insulated Gate Bipolar Transistor is a very efficient device capable of switching high currents and voltages in a very small, cheap package. Thus, the Einsteins have replaced my StopLights as my flash of choice.

While using the Einstein flash units in my hummingbird photography, I found that much longer flash durations would still freeze the wings. The 78µs requirement that had been calculated above is equivalent to around 1/13000th of a second, yet even at a flash duration of 1/7000th of a second with the Einstein, wingtips would be frozen mid-flap, most of the time. Assumptions were clearly incorrect.

Analysis Using High Speed Video

Male Allen’s hummingbird photographed with a flash duration 1/7000th of a second

The use of a high speed video camera enables us to accurately and simply determine the wingbeat frequencies of any birds we capture footage of, so I put one to work...

You can see the analysis process here.

Scenario

Hadland Imaging Inc. sells and distributes high-speed imaging equipment, including products from iX Cameras – the leading high-speed video company in terms of speed and resolution. For this experiment, we used iX Cameras' i-SPEED 720 monochromatic and i-SPEED 726 color cameras. These cameras are easy to set up and use, widely flexible in their applications, and offer the best value and performance available.

Light Sensitivity of High-Speed Video Cameras

The sensitivity of the i-SPEED 726 is astonishing. The ability to create 5000 fps clips of hummingbirds in natural light could only be dreamed of until recent years. The PBS documentary Flying Jewels produced in 2015 used high-speed cameras exclusively to create slow motion footage of hummingbirds in wild surroundings. While the hummingbirds appeared to be in wild environments with natural ambient lighting, observant viewers noticed that most of the footage was created in studio conditions with very high intensity artificial illumination. If the documentary was produced today, high intensity illumination would be far less essential, and the hummers' movements could actually be captured in the wild.

Camera Setup

Camera pointed at hummingbird feeder in Westlake Village, Southern California

The camera is on a tripod a couple of feet away from a hummingbird feeder and connected to the iX Cameras CDUe (Control Display Unit) which can configure, focus, change shutter speed, trigger and download footage from the camera. Both cameras were equipped with standard Nikon F mounts. For this experiment, a 105mm Nikon lens was used.

Ethics

To a wildlife photographer, ethics are hugely important. Coercing or cajoling a subject into behaving ‘for the camera’ is not ideal; however, it has been done for eons. Fortunately, the technological developments that we have seen in high-speed video are minimizing and even eliminating the need for this.

Analysis Method

Once the high-speed footage has been captured, several software packages are available for motion analysis. Xcitex provides the leading package, ProAnalyst®, and an engineer from Xcitex performed the analyses.

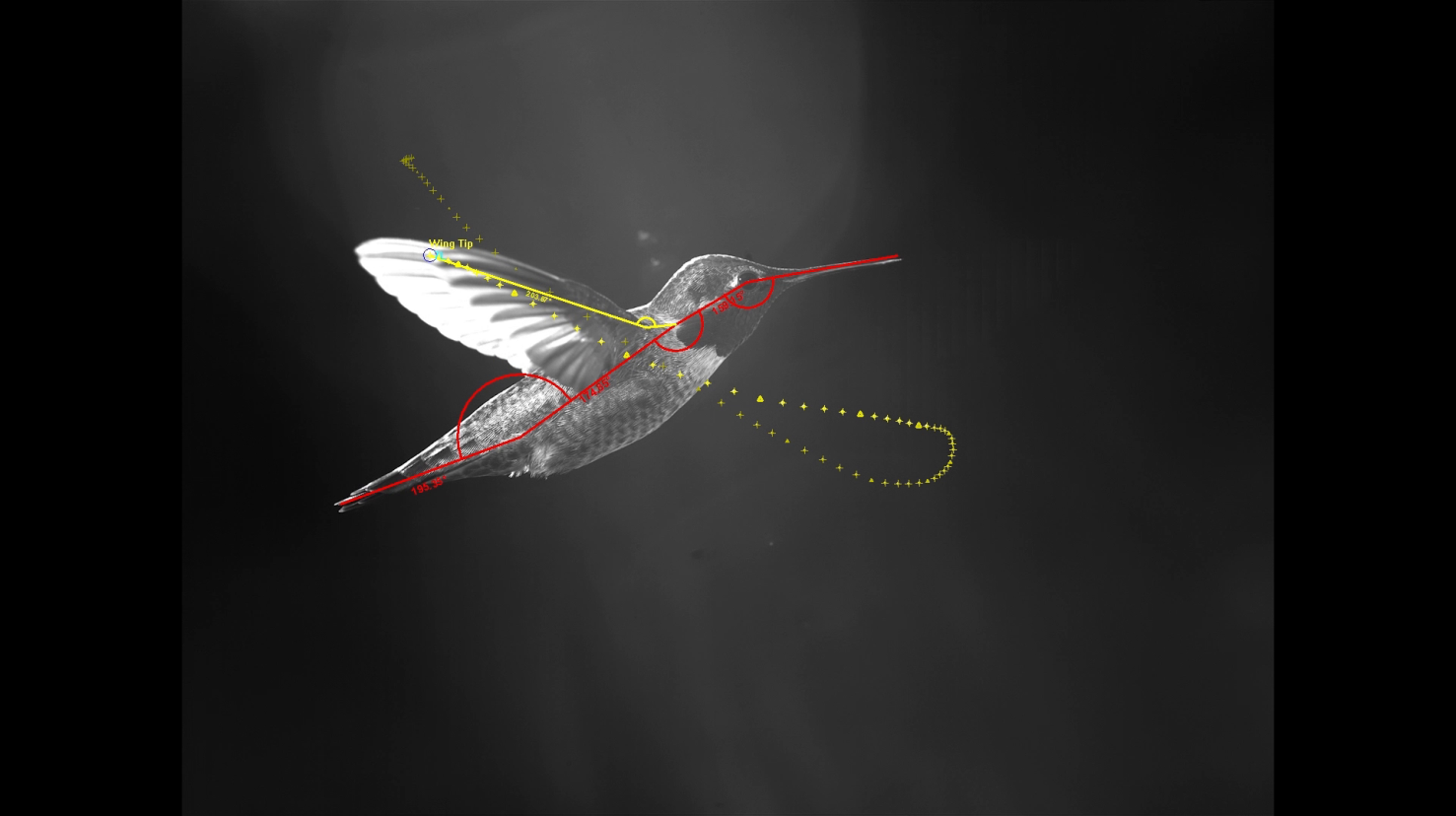

When a clip is captured by the i-SPEED 726, a data file is created containing all the parameters associated with the clip: frame rate, timestamp, resolution, aspect ratio, trigger information, etc. It is a relatively straightforward process to highlight a wingtip in a single frame, and the ProAnalyst software tracks its motion and automatically measures the period between the peaks of the amplitude of travel. The inverse of this period is the wingbeat frequency. An expert user can process many clips and quickly obtain highly accurate results.

Results

The results obtained from this experiment confirmed my original suspicions that hummingbirds in Southern California have wingbeat frequencies about half of what was often cited in the lay press and literature. More research has been performed since I first started photographing hummingbirds, and a Google search shows that many hummingbird wingbeat frequencies are in the 35-60Hz range, far slower than originally thought. This proved that the original design parameters for the StopLight SL-80 were overkill in terms of flash duration. Had this been known, the design of the flash units could have been radically simplified and the cost reduced.

Male Allen’s hummingbird photographed with a flash duration 1/7000th of a second

Male Allen’s hummingbird photographed with a flash duration 1/7000th of a second

Camera pointed at hummingbird feeder in Westlake Village, Southern California

Camera pointed at hummingbird feeder in Westlake Village, Southern California

An overview of this process featuring analysis footage of Annas hummingbirds is available on Xcitex’s YouTube page:

An overview of this process featuring analysis footage of Annas hummingbirds is available on Xcitex’s YouTube page: